by Holly Hardman

The Alaska Airlines door plug disengagement horror at the start of 2024 has prompted a lot of questions about aircraft safety and oversight. Thank heavens all on board Flight 1282 survived. I would bet that every person on the plane watched their lives flash before their eyes while sitting frozen near a gaping hole at an altitude of 16,000 feet. Terrifying. I would also hasten to bet that every single person on the flight is now dealing with trauma.

The craft, a Boeing 737 MAX, has a checkered history. The 737 MAX was cleared for flights in the U.S. in 2017. The planes have been plagued with manufacturing errors and safety issues for years. In 2018 and 2019 there were near concurrent 737 MAX crashes with no survivors, one in Indonesia and one in Ethiopia.

For a relatively brief twenty-month period, the Federal government did not allow 737 MAXes to fly. Then, in a flawed and corrupt testing process, Boeing and the FAA colluded to get the 737 MAX back in the air. The planes were cleared for a return to service in November 2020. After the recent debacle on January 5, the 737 MAX is grounded again.

[Update Jan. 24, 2024 ] Well, that didn’t last long. The FAA has agreed to allow the 737 Max to fly again after rigorous inspections have been performed. That’s pretty quick. Though in a move that suggests an attempt to address Boeing’s ongoing quality control issues, the company will not be allowed to continue the manufacture of any planes in their production pipeline, according to FAA Administrator Mike Whitaker, “until we are satisfied that the quality control issues uncovered during this [inquiry] process are resolved.” (NPR)

It has been widely reported over the years that Boeing and its manufacturing partners were cutting corners to meet impossible delivery orders. The pride in engineering that had defined Boeing’s leadership in its early years had been replaced with Wall Street-driven leadership that valued the bottom line dollar. A rabid chase for high profits overrode concerns for sound design and safety.

To the benzo-harmed community this sounds regrettably familiar.

We in the benzodiazepine and pharma-harmed community know only too well that life is cheap when profit is the paramount motivator. A loosening of ethics too often prevails and a dedication to product quality and safety can too easily go by the wayside. The lost lives of the harmed are just the inevitable casualties of making money for CEOs and shareholders.

Looking back on the early days of Hoffmann-La Roche (Roche), the company responsible for the first benzodiazepines, Librium and Valium, it is clear that it was an entity, like Boeing, that took pride in the application of discovery and good science.

In 1896, when Hoffman-La Roche opened in Basel, Switzerland, the company first introduced a thyroid medicine called Aiodin, which was soon followed by a general cold medicine called Siroline. It appears that Aiodin helped and Siroline did no harm. In 1904, they introduced Digolen (digitalis) for the heart. In 1909, they started producing an opium-like analgesic called Pantopon. There were instances of kidney dysfunction and even psychiatric issues related to digitalis ingestion, and Pantopon held similar risks to morphine. At that time, Roche did not seek to hide the risk-to-benefit ratio. The company did not deny the risks or seek to market them using deceitful information as they did with benzodiazepines in later decades.

World War I disrupted Hoffmann-La Roche’s early prosperity, but once the war was over, the company picked up steam again with useful vitamin compounds. They also released a barbiturate derivative called Allonal with the proviso that it was for rare use only. And records indicate that doctors followed that directive.

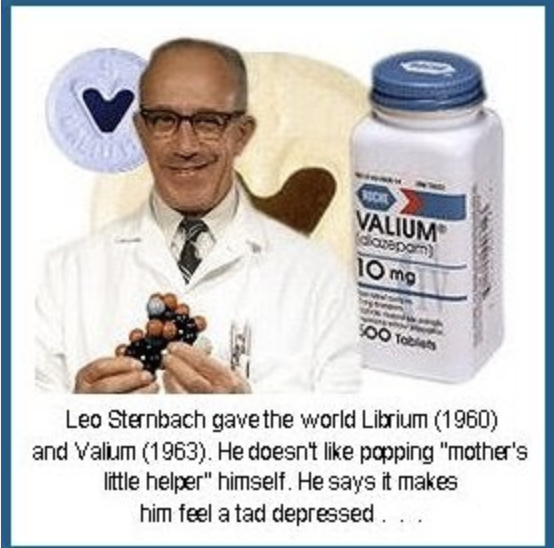

Their real bread and butter came from their vitamin formulations, and this remained steady until the post-World War II years when the allure of calming tranquilizers like the wildly popular meprobamates Miltown (Wallace Laboratories) and Equanil (Wyeth) tempted Hoffmann-LaRoche to explore anxiolytics. The company’s good fortunecatapulted Roche into the arena of immense fortune quite by accident when scientist Leo Sternbach and his research team observed an arresting change in the synthesis of an earlier dye experiment. Based on the molecule’s structure, it was called chlordiazepoxide and, as suspected, when tested, was shown to have tranquilizing power.

Chlordiazepoxide was released with the brand name Librium in 1960, and was followed shortly after by the more potent benzodiazepine Valium (diazepam). Things were never the same. Valium and Librium eclipsed Miltown (meprobamate) sales and benzodiazepines became the world’s most popular class of tranquilizers.

Sternbach was a dedicated scientist and an ethical person and what the company did with their new discovery was not Sternbach’s call. He was merely an employee, albeit an irreplaceable one, at the company’s Nutley, NJ headquarters. Sternbach’s bosses paid him $1 for the patent and gave him a $10,000 bonus. That’s it.

The story turns sordid when Roche corporate leadership ignores evidence of the drugs’ adverse effects and then hires Arthur Sackler to market Librium and Valium with an eye on pure profitability. (Not coincidentally, Arthur Sackler was the progenitor of the Purdue Pharma Sacklers, who are directly responsible for the nationwide opioid epidemic).

Arthur Sackler’s marketing methods were pure 1960s advertising genius. Both Librium and Valium were blockbusters. Valium was the pharmaceutical industry’s first $100 million-selling drug. In 2024 dollars, that’s just under $900 million. And the numbers have grown exponentially over the years. Current sales globally now exceed $3 billion annually.

Knowing how insidious and damaging benzos can be, it’s no surprise that news of adverse effects eventually reached the light of day via patients reporting their nightmarish problems with Librium and Valium to doctors, media connections, government agencies, and legislators.

It was the Sixties, and Americans were taking and experimenting with drugs as they never had before. The psychoactive substances, some legal and some illicit, ran the gamut; they could be helpful, harmful, stimulating, calming, enlightening, dangerous, or addictive — drugs like marijuana, LSD, amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and heroin. Congress determined that societal and medical problems caused by this spectrum of drugs called for action, a special set of laws to regulate them.

In January 1970, the Controlled Dangerous Substances Act was introduced. The bill categorized drugs of concern into four distinct types that corresponded with degrees of usefulness and danger. As the bill was initially laid out, Valium and Librium were placed in Schedule III with amphetamines and short-acting barbiturates. Schedule III drugs had been shown to be useful medically but did pose a risk for abuse and dependency.

This rattled the top brass at Roche. To compel legislators to ease restrictions on their highly profitable Valium and Librium, Roche hired attorney Joseph Califano to lobby on the company’s behalf. Califano’s long career in law and government service once included time as a powerful lobbyist for corporate interests and Hoffman-La Roche had been one of his major clients.

To build his case, Califano scoured benzodiazepine research. He cherry-picked salient points and presented the argument that benzodiazepines did not create dependency and did not contribute to suicide. He also left out their interaction problems with alcohol and other drugs.

As a result, the final version of the bill included five schedules, with one created specifically for benzodiazepines, Schedule IV. Schedule IV contended that benzodiazepines had medical use, but, unlike the more dangerous Schedule III drugs, had low potential for abuse and dependence.

For this success, Roche rewarded Califano with a half-million dollar bonus.

In his book INSIDE, A Public and Private Life, Califano, recalling Sen. Edward Kennedy’s 1979 Senate hearing on benzodiazepines and Barbara Gordon’s bestselling book I’m Dancing as Fast as I Can, writes with regret: “To this day, I wonder how many patients developed problems as a result of my lobbying to keep these tranquilizers free of stricter controls. I remember it as a dark moment in my private practice of law.”

How many? Millions. And it’s still happening. Everywhere.

Corporations have become inadequately regulated profit machines.

The FAA appears to be making moves to change that. All Boeing 737 MAX planes are grounded indefinitely. The FAA is set to take a new approach that removes self-interested parties from the inspection and determination process. I hope they can hold to that.

After all, there is a lot of money involved. Again, the profit motive.

Current times might be demanding better — not merely a return to a negligibly better culture of earlier days, but to a refreshed paradigm, as corporations start to operate with a much more concentrated eye on quality, safety, and ethics.

Now that the FDA seems to be acknowledging a complex benzodiazepine injury syndrome, will they adhere to improved safety regulations and oversight for benzodiazepines? Will the pharmaceutical industry work together with the healthcare industry to put restrictions and programs in place so that benzodiazepines are not overprescribed and people who find themselves suffering from adverse effects have easy access to benzo-wise treatment and care? I am not suggesting that the manufacture of benzodiazepines be discontinued. Though I would rethink that if the necessary cautions are not put into place soon enough.

The benzo-harmed are not at risk of falling out of a plane in the sky while in active benzo withdrawal or living with Benzodiazepine-Induced Neurological Dysfunction (BIND). But many live with internal sensations that feel similar, like an unrelenting sensation of being stuck on a rocking boat. Those with benzo-induced akathisia can be thrust forward, experiencing a strange self-propelled jolting or internally forced non-stop pacing. There can be a frightening compulsion to jump that the sufferer manages to suppress. Sometimes suppression is not possible. There are leaps out of buildings and off bridges.

The community lost another member this week. Joey Marino.

When I first heard of Joey, Geraldine Burns was trying to help him. He was terribly ill but there was hope. Geraldine advised against a rehab hospital he was being coerced into going to in Alabama. He felt forced to go. The rehab hospital’s polydrugging treatment seemed to have made him irreversibly ill.

One of Joey’s posts from last year on X:

May 14, 2023

“I have severe tardive Dyskinesia and Dystonia and most of my body is numb and my mouth never stops chomping down… I am so scared, I’m on Klonopin and two other drugs once a Parkinson’s drug… I don’t know what to do. I’m in such pain.”

Joey was in agony with no control over constant twisting, shaking, and palsy-like movement. He’s gone now. He left quietly in the middle of the night.

At least he was with a friend. Rest in peace, Joey.

To arrange a screening of As Prescribed, please contact us at aspresribedteam@gmail.com or fill out this form. Contact The Video Project for educational and community screenings.

—Holly Hardman, Director/Producer of As Prescribed